In the past, Noah’s ark shells (Arca noae) lived significantly longer and grew more slowly, whereas today, under strong human influence, they grow faster and have a shorter lifespan. This is shown by new scientific research based on the analysis of fossil shells that are several thousand years old.

Researchers from the Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, in collaboration with partners from Austria and Slovakia, analysed fossil remains of Arca noae from the northern Adriatic Sea. The results of the study were published in the prestigious international scientific journal Continental Shelf Research.

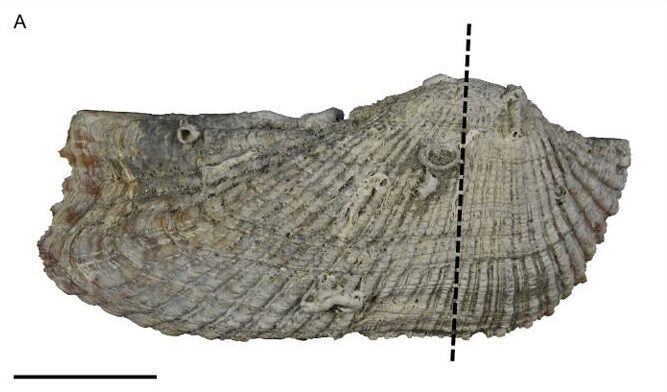

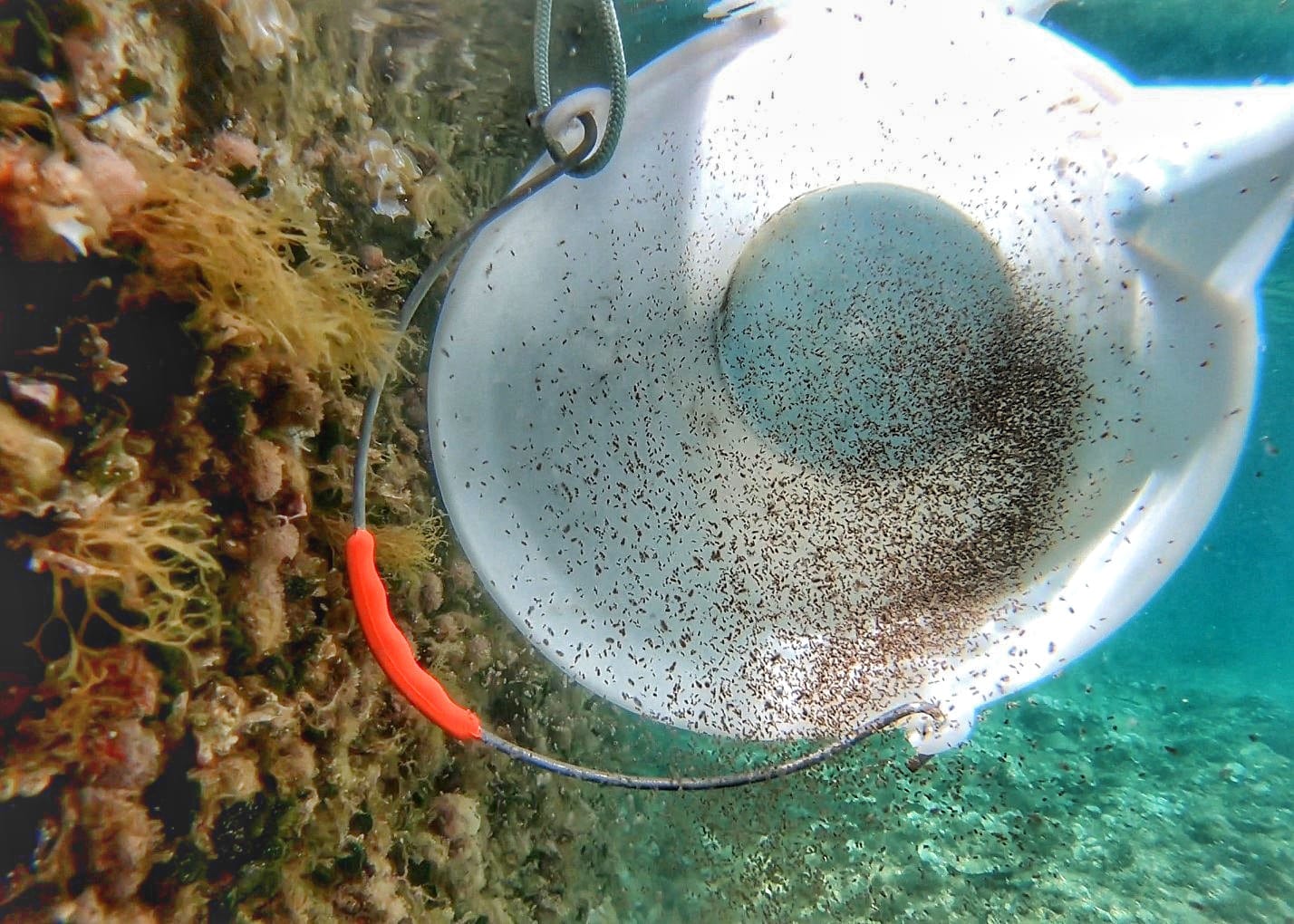

To reconstruct the lifespan of these bivalves, scientists extracted sediment from the seafloor containing preserved fossil shells. Their age was precisely determined using radiocarbon (C-14) dating, after which annual growth lines in shell cross-sections were analysed in the laboratory.

Based on these data, the oldest analysed A. noae specimen was estimated to have lived at least 85 years. The authors emphasise that this is a conservative estimate, as bioerosion and shell damage meant that only clearly visible annual growth lines could be counted in some fossil shells. Some individuals may therefore have lived even longer. In modern times, by contrast, the oldest recorded A. noae lived only 35 years.

In the past, Noah’s ark shells were intensively harvested and represented an important food resource for coastal communities. However, in the mid-20th century, a major mass mortality event occurred which, together with subsequent increases in sea temperature and enhanced nutrient input via river inflows, permanently altered the structure and life-history strategies of their populations.

Bivalves are both ecologically sensitive and economically important organisms. Studies such as this help us understand their true long-term history, rather than using periods already heavily shaped by exploitation and other human pressures as a reference baseline.